16 Ways The Book of Dust Is Sir Philip Pullman’s Star Wars Prequel Trilogy

One difference between British fantasy author Philip Pullman and American film director George Lucas is that Philip Pullman is a good writer. One similarity between Pullman and Lucas is that they both decided, many years after concluding their respective groundbreaking, critically-hailed, widely-beloved, and highly lucrative three-part works of fantastical entertainment for children, to do a second trilogy.

George produced the furiously-hated Star Wars prequel films, for which I am a lifelong apologist. Philip produced The Book of Dust, an enwrapping prequel-sequel series to His Dark Materials, for which I anticipate becoming a lifelong apologist.

In reading all three installments of The Book of Dust (La Belle Sauvage, The Secret Commonwealth, and The Rose Field) back-to-back-to-back last week I discerned some notable similarities between Pullman’s latest trilogy and Lucas’ late works, though I didn’t put the pieces together until I visited a Reddit thread on r/hisdarkmaterials full of seething fans, where I found them throwing around accusations of “Star Wars prequel level badness”. This discourse enthralled me.

In the following listicle, I shall enumerate the commonalities I see between The Book of Dust and the Star Wars prequels. Though I rarely place a spoiler warning on my work on account of 1) being an asshole, and 2) almost always treating upon well-aged material, for once I will say loud and clear: DON’T READ ANY FURTHER IF YOU CARE ABOUT SPOILERS FOR THE ROSE FIELD OR ANY OTHER WORK RELATED TO HIS DARK MATERIALS.

Now, onward.

One: This trilogy wasn’t, strictly speaking, necessary

We must address and accept this point immediately: no, there was no compelling reason to make more His Dark Materials, any more than there was a compelling reason to make more Star Wars. His Dark Materials, which I shall hereon abbreviate as HDM, was thunderously conclusive in its ending, tying up every element of the story that I recall and delivering a clear and cogent thesis. It is a book in which the protagonists literally kill Christian God. There’s nowhere to go, and nowhere we need to go, from killing Christian God.

However, authors do need to get paid. Also, your creative types, myself included, don’t like to move in predictable or rational ways (actually, this is part of the narrative of The Book of Dust’s latter installments). Philip Pullman had a certain set of things he wanted to say, a certain amount of money he wanted to make, and a certain set of tools lingering in his box: the characters and setting of HDM. In the same way, George Lucas, distressed by the slow American slither into authoritarianism and seduced by innovations in cinematic special effects, deployed his Star Wars toys anew in 1999 despite no one in the whole world needing to know what the “Clone Wars” were really like.

Two: Everyone’s mad at him because they just wanted to see more Darth Vader

Read “Darth Vader” here as “Will Parry”.

This point is almost self-explanatory to anyone who has read HDM, especially as a child, but let it never be said I missed a chance to be pedantic. Between the release of the original trilogy and the release of this new trilogy stretches a gulf of tweeny sorrow into which multiple mini-generations of children have tumbled as they learned about the intractable grief of the world via Lyra and Will’s final separation. The young HDM fan naturally has a tendency to imagine that a sequel would correct this injustice and return the young lovers to each other.

Note the load-bearing double “young” in that previous sentence. As an adult, I quickly intuited that the man who--let us recall--prescribed the killing of Christian God as a good solution for bettering the multiverse was not about to throw us a big juicy bone when it came to love triumphing over all.

And he’s right! Pelt me with tomatoes all you want, but I stand by the idea that the love one first feels at thirteen or fourteen is not likely to endure, perhaps ought not endure. Not in the fashion of an ongoing romance, at least. Darth Vader (Will Parry) does not appear even one time in The Book of Dust stories, and that is unequivocally fine.

Similarly, though Darth Vader appears in the Star Wars prequels at length, he is in the form of the mewling, miserable Anakin Skywalker, a sad and demented creature who reveals cinema’s coolest ever villain to be evil primarily on account of being a mega-loser. As I’ve aged, I’ve come to appreciate this depiction more and more. If there’s one thing the world has taught me between the release of the prequels and now, it’s that the bitterest, cruelest, most flagrant villains of real life are also always the lowest and most embarrassing people you know. But the Star Wars fans of the fin-de-millennium couldn’t handle this revelation because they wanted to see Darth Vader looking cool.

I’m aware that I’m clobbering a strawman with my depiction of the average 2002 Star Wars fan. I have no intention and no requirement to provide fair and balanced coverage here.

Three: The concepts of “canon” and “retcon” are not clearly not important to him

In The Rose Field, Pullman changes his mind about several key elements of HDM, most notably the idea that all the windows between worlds need to be closed to preserve conscious life. This was, of course, the reason Lyra and Will were separated so tragically at the end of HDM.

But that isn’t the only reason they were separated. We also learned that beings from one world can’t thrive in another. We also, and I cannot stress this enough, all knew that Lyra and Will were thirteen.

I did genuinely see someone on Reddit comparing this change to the nature of the windows to the midichlorians in The Phantom Menace. It gave me the gigglies.

A significant portion of the second and third installments of The Book of Dust is spent investigating the pernicious influence of post-Enlightenment man’s obsession with rationality and certainty, with orderly knowledge of an orderly world which can be quantified and assigned absolute values for all its constituent parts. The universal fan obsession with canon-compliance and enforcing order on imaginary worlds is a type of pernicious overly-Enlightenment-ed thinking. A general internal consistency is good for secondary world storytelling, but any further rigidity of world is up to the discretion of the storyteller and the kind of story they want to tell. Why are you, the fan supposedly doing this for fun, building cops inside of cops inside of cops inside your mind?

Fictional canon is best taken as something to laugh about. When it doesn’t make sense, we might say “haha the old man forgot what he said before”, or “hmm I wonder what the old man means by that”. If I ever say “how dare the old man say the thing he made up is different from what he said it was before” in a sincerely angry tone of voice, you have permission to knock my block off.

I’m not saying that I completely buy the changes Pullman makes to the meaning and function of the windows, but I do think there are several ways to interpret and explore what he says about them in The Rose Field. For the time being, I’m going to do as folks in the 1970s did and hang free on it.

Four: He has a lot of urgent and relevant things to say about Our Times

In 2005, everybody laughed when Padmé said “So this is how liberty dies: with thunderous applause”. Well, now we’ve swallowed twenty more years of Patriot Act-ion and I look like the eyebags emoji. Fuck you, George Lucas, for being right and not doing anything about it despite your enormous fortune. But that’s a different post, I’m losing the thread.

What I’m trying to say here is that, despite being a terrible writer, George Lucas has proven a surprisingly prescient observer of Our Times. The prequels are in some ways a tale told by an idiot (later retold by a smart person named Tony Gilroy in the form of Andor) but the prequels do signify something, though you have to really want it in order to receive that signification as anything meaningful.

Similarly, the changes in Lyra’s world since the original HDM trilogy speak to the mutations and mutilations of our world in a variety of ways. The mystical beings detect strange changes to the air and the sea. Sicknesses of both physical and spiritual natures spread over the land. The Magisterium, though still dressed up in its religious clothes, has become more and more a simple exertion of force running through all the governments of Europe and Southwest Asia. Dangers empowered by religious extremism, perverse desire, greed, and every other vice swarm up from all sides.

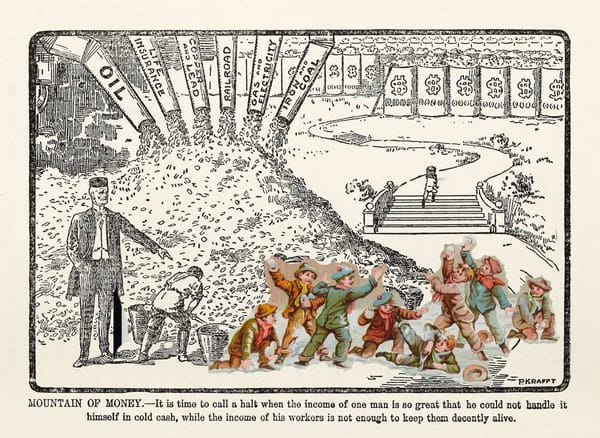

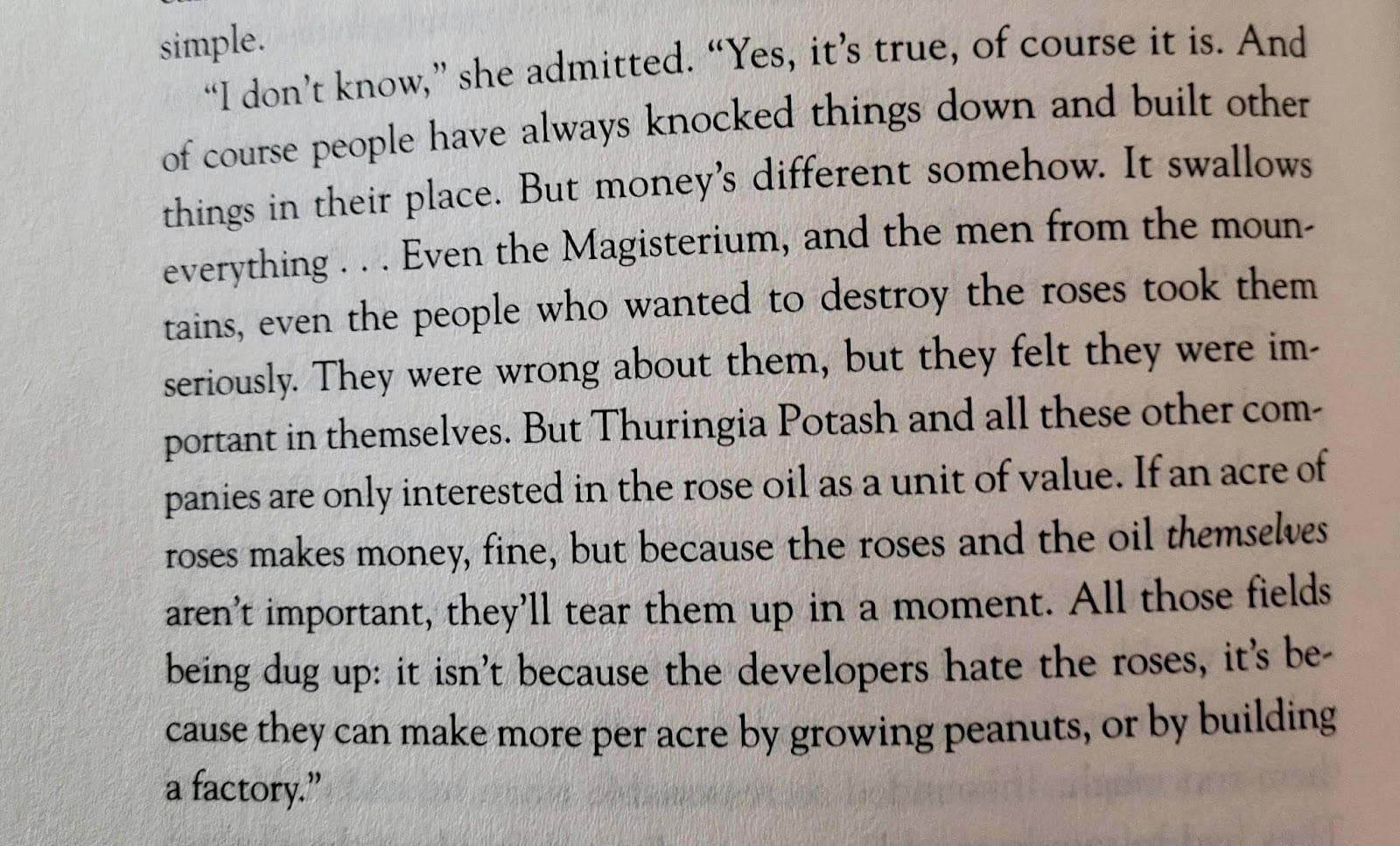

In the end our heroes discover that the worst of these enemies is the destructive effect of untrammeled capitalism on the foundational parts of the human spirit. They find the transcendent beauty they sought throughout the narrative already paved over by people who can’t see their own daemons anymore, only their plans for perfected and efficient transaction. Lyra and Pan and their friends don’t defeat capitalism, either. At the end of The Rose Field, they sit down to take a rest and begin to discuss what they might do about it.

This is not a very satisfying or Campbellian conclusion to a roughly 1800-page epic built upon a previous many-pagéd epic, but it is, I have to say, quite worth saying. It reflects the viewpoint of a man who is old and not likely to see the outcome of this most real fight. He doesn’t know what we are going to do, but he has written an invitation for you to pitch in with it because it’s not likely he’s gonna be the one carrying us over the finish line.

Five: He is being both maddeningly subtle and bonkingly didactic throughout

There are books within books in these books. The seductions of rationalism and post-modernism are dissected via the popular philosophical literature of Lyra’s world and the foibles of the books’ authors. But I am again still hanging free on the metaphorical significance of these books; which philosophical works from our world they correspond to mostly closely; how their arguments interlace with the psychic damage caused by late capitalism Pullman depicts later in the story.

On the other hand, this is how Philip treats on the pernicious nature of capitalism:

To be honest, I can’t even say George Lucas is ever maddeningly subtle, certainly not to the same degree Philip Pullman is. But as I said in the previous point, one does have to do the work to make his prequels mean something. There is much to learn in any work. Only Sith deal in absolutes...

Six: He has so many characters he wanted to tell us about

Something I admire about both Philip Pullman and George Lucas is their mutual facility at making up interesting guys with memorable names and looks. They never stop dropping excellent new dudes upon us, and cutting around the storyworld with abandon to show us said guys.

In The Rose Field, Pullman goes big on cutting around the storyworld, often showing us characters several times without necessarily providing a punchline for why they’re in this book. This is, to be clear, annoying and confusing. But I have to concede that for his purposes he is right. One of the chthonic-level themes of this book can be summed up by the adage I most recently confronted in Little, Big (speaking of impenetrable auteur visions): The center is everywhere, the circumference nowhere.

While the final problem our heroes confront is too big to be defeated by them alone, the web of beings which partake of the titular Rose Field and which stand for the side of good is world-spanning. The center of Lyra’s world for us is Lyra. But the center of her world also resides within every other conscious being.

Pullman already did a multiverse-spanning war in the first HDM trilogy. Multiverse-spanning wars are, to be honest, getting a bit cheap of late. Dime for a dozen, as they say. Though Pullman’s narrative movements remain confined to one universe during The Book of Dust, they point to something even larger and much, much harder to put into words. The center is everywhere; the circumference is nowhere.

Seven: The first installment is wet and the most important character is notably young

This is a really straightforward comparison: in The Phantom Menace they go underwater a bunch and hang out with Jar Jar, an amphibian. Anakin, AKA Darth Vader (not Will Parry this time), is ten years old.

In La Belle Sauvage, Oxford gets flooded by a monumental storm and Malcolm Polstead, a local kid, has to rescue Lyra, who is a baby. They go upon water a bunch.

Eight: The second installment is emotionally oppressive and confusing

Attack of the Clones has a very bad rap. Some critics have called it George Lucas’ Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis. I, a noted prequels apologist, didn’t finish it the last time I watched it. It’s full of many scenes of stuff, almost all of which is rather depressing and confusing. Anakin commits a genocidal hate crime, but we’re supposed to still be somewhat onboard with him. Anakin and Padmé fall in love despite their weird age gap and his total unsuitability as a partner to anyone. Obi-Wan finds out that there is a clone army belonging to the Jedi for…reasons?

The Secret Commonwealth is better than Attack of the Clones (if we can compare books to movies). But it is also quite dark and dense. Lyra sets out to cross a continent because despair has driven the best part of herself away. In her journey, she falls prey to the many depredations of a heartless, violent world. It feels bad. Also, Malcolm from the previous book, who is thirty, thinks he’s now in love with Lyra, who is twenty. We’ll get into that later.

Nine: The third installment delivers a climax that frustrates fans who had wildly different expectations

I think Revenge of the Sith is the best-liked of the prequels, while I’m getting the sense HDM fans are most mad about The Rose Field, so my comparison pretty much breaks down here.

Nevertheless, I forge on. Revenge of the Sith was supposed to conclude Anakin’s journey into Darth Vader-hood, making him the cinema’s most badass villain ever. Yet, in the sharpest of George’s insights, Anakin is still a whiny loser throughout. There’s also an extended thread where Yoda and Chewbacca hang out. I think it rips, but I agree that it answers no interesting questions and facilitates no meaningful revelations.

I suspect many fans believed The Rose Field would conclude Lyra’s journey by 1) reuniting her with Will as discussed above, and 2) having her save the world again. But she is an adult now, and she has adult problems. The world confronts her, and she finds out what she needs to do. Luckily, unlike for Anakin, it doesn’t involve killing the younglings.

Ten: There’s some behind-the-scenes production drama that I don’t care about

I’m hearing some rumors that Philip Pullman’s editor made him rewrite the last part of The Rose Field. I don’t care. I will not be joining #ReleaseThePullmanCut. I’m encountering the text I have and I’m making meaning out of it.

I’m pretty sure there’s also behind-the-scenes drama around the Star Wars prequels, but I might, as I often do, be confusing the prequels with Megalopolis. Once again, I don’t care.

I’m interested in Megadoc exclusively. Don’t @ me about behind-the-scenes drama unless it starts with “Francis F” and ends with “ord Coppola”.

Eleven: There’s multiple relationships everybody’s mad about (but is he incorrect?)

Okay, now we really get into it. In the second book Pullman tries to set up a relationship between Malcolm and Lyra, and it doesn’t work. I did not like it the first time I read The Secret Commonwealth, and I didn’t like it when I reread the books last week. HOWEVER, I do buy it. I do believe a thirty-year-old guy could have some inappropriate feelings towards his younger female former student. I do believe that Lyra, a person with level-red daddy issues, might make questionable choices about her relationships with older men, especially when she is hung up on a former partner and very lonely.

In the end it works out in a way I did appreciate: Lyra realizes she just doesn’t like Malcolm that way, and Malcolm accepts Lyra can’t and shouldn’t reciprocate his feelings. They’re just friends who’ve been on several adventures together. Sometimes you and another person have a whole set and arc of feelings toward each other, and that process is complicated and doesn’t come to anything with a name. Sometimes it’s better that way. I am glad to have someone write about this, even clumsily.

I suspect many are also cheesed off by the revelation that Olivier Bonneville is Lyra’s long-lost half-brother via the union of Mrs. Coulter and Gerard Bonneville. This twist drew more accusations of Star Wars-coded behavior. I found it a truly out-there addition. It is another point upon which I am hanging free. Olivier ends up being the real hinge of the Magisterium plotline while Lyra is busy discovering the corrosive effects of capitalism. That’s interesting. In the end, though Olivier is a pretty unlikable little dude, he reconciles with Lyra and they end the story together. The last emotional note is a sibling one.

If you asked me now to interpret that decision on Pullman’s part, I would say that Olivier is representative of the sort of person Lyra would be if she’d grown up under the direct pernicious influence of her shitty parents, shitty uncle, shitty grandmother, and the Magisterium. He’s selfish, shallow, enamored of his talents to a disproportionate degree. It kinda seems to me like his uncle molested him and that messed him up further. By contrast, Lyra grew up in the scholarly warmth of Jordan College, surrounded by caring, attentive people who believed in the value of knowledge, effort, and truth. She sees people for who they are and considers them as people. As an adult, she tries not to instrumentalize them, her parents’ most favorite activity ever. Olivier never got to learn these things. He grew up in a very cold world, and Pullman succeeds, in my eyes, in making him a pathetic but also sympathetic figure. The reconciliation between Lyra and Olivier is a testament to her maturity and her ability to now help someone who faces trials that she might have faced earlier in her own life.

Or not, I dunno. But this is more fun than receiving a god-core proclamation from the author about how we must relate Lyra and Olivier.

I feel the same way about Star Wars relationships like Padmé and Anakin. Is their chemistry nil? Yes. Are their relations melodramatic? Yes. Do all of us know one smart, lovely, talented young woman wasting her life on some reactionary jerk? Yes, some of us have even been her. I am grateful to George Lucas for planting a seed in my mind to remind me that the consequences of dating said reactionary jerk might be that he kills you in a fit of pique. Perhaps life is more important than mere romantic love.

Twelve: Fans desperately wanted it to be more of their childhood, but it wasn’t

Another cAnoNicAL point of order Pullman demolishes in The Book of Dust is the taboo about touching other people’s daemons. Several different characters touch each other’s daemons, in emergencies and in emotional moments, and while the feeling is intense it is not unwelcome, life-altering, or a bitter violation. As an adult with agency, Lyra experiences these encounters differently than she did as a child.

Gosh, I wonder if there’s any sort of real world human relation which might have an allegorical or metaphorical connection to the touching of another person’s daemon. It’s on the tip of my tongue…

Never mind.

The Book of Dust is not the same trilogy as His Dark Materials. This is fine. Lyra is an adult now; she is someone other than the kid we left behind at the end of The Amber Spyglass. This is fine. Philip Pullman had something else he wanted to say, and he didn’t want to pick up exactly where he left off with HDM. This too is fine.

The original Star Wars trilogy is a space adventure about a dork and his friends blowing up a spherical WMD. The second Star Wars trilogy is a political drama about a little boy who becomes a mass murderer. This is fine.

Have your fun, old man.

Thirteen: “Fantasy” =/= “Makes You Happy”

This actually has nothing to do with Star Wars, I just wanted to bitch about it. The genre of Fantasy makes no inherent promise to make you happy or produce good feelings in your heart and tummy. I know there are publication genres like this. My understanding is that Romance is like this. Chicken Soup is like this. Fantasy isn’t necessarily like this. Fantasy is about occurrences and elements which cannot possibly happen in our consensus reality.

If you wanted to read a book with the Fantasy genre sticker on it which is sure to make you happy, may I again recommend humbly that you give a pass to books by the man who wrote a children’s fiction series about killing Christian God?

Fourteen: The trilogy ends in sadness

Back to Star Wars. The prequels end in sadness: Padmé dies, Anakin turns evil, all the Jedi are killed, and the Emperor attains ULTIMATE POW-AH! We carry on with the last hope of Luke and Leia, hidden in the far-flung reaches of the galaxy.

In the case of Star Wars, we do have the original trilogy promising us relief in the future. In the case of The Book of Dust, when Lyra discovers that capitalism is undermining the whole fabric of human consciousness, there’s nothing she can do in that exact moment to save us. She has her friends, she has her daemon and so her self, and she has her vocation: discovering the truth through the reading of symbols. But she doesn’t have the opportunity to make humanity’s last stand. Nobody does. We have to muddle through now, and so does Lyra. That’s honestly sadder than Anakin being evil, to me.

Fifteen: Imperfections are a hand to hold

I must reveal a terrible secret: your creative projects aren’t going to turn out perfect every time. Things that made sense in your head won’t make sense on the page, and they won’t make sense to the audience. Not everyone will get it. Maybe nobody will get it.

I don’t know if Philip Pullman will have time to write another epic trilogy, or if it will be good or bad. George Lucas didn’t feel like doing it a third time. But I’m glad they decided to take a second swing. The world is more interesting for it. I feel less afraid of failing.

The pacing of The Rose Field is weird. There is so much about gryphons and sorcerers which doesn’t feel immediately relevant to the main conflict of the book. Many things transpire offscreen or indeed after the book ends which most of us would have liked to hear about directly. Multiple things come flying in from left field at inexplicable moments. The ending of His Dark Materials is not reversed or reoriented or reiterated or addressed at all, except very subtly.

Sixteen: I’m not mad about it; in fact, it gave me heart

The Book of Dust trilogy is made up of messy and wild books, with all kinds of bits and bobs and strange bits. I’m not mad about it, I’m glad about it. Philip Pullman didn’t waste my time! He tormented and baffled me at times, he made me bash my head into the wall repeatedly, and he blatted all over the place. We had fun, though, the whole time through. We talked about all the pressing questions which have beaten against the inside of my head these recent months, and in the end Philip Pullman helped me answer them. I couldn’t have answered them alone, not in the way I have now. We sat together in the Rose Field.

You can’t always have what you most desire. You will have to grow up. It was actually Philip Pullman who first told that to me, a long time ago.

If you’d like to read more about The Rose Field from critics who prioritize “coherence” and “not doing a stupid bit the whole time”, I recommend Lev Grossman’s review in The Atlantic and Rowan Williams’ review in The Observer. Kisses also to the person who linked these over in the seething Reddit board where I found them.