Recently Reading Hugo Nominees, Part III

At last, at last, at long last: I have concluded my read of the 2025 Hugo Best Novel nominees. It got…a little bit easier here at the end. There were some weird mushrooms and freaky beasts. But there were also unexpected challenges.

The Tainted Cup by Robert Jackson Bennett

My sister and I at times engage in a behavior we call “Romancing Morrowind”. Romancing Morrowind is a type of maladaptive daydreaming/dependency behavior rooted in our early childhood exposure to the Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, Bethesda Softworks’s fin-du-millénaire open-world sandbox fantasy game. Morrowind is a famously alienating game, with confusing, poorly implemented mechanics; a hallucinatory low-res visual style; and lore famously written by a Religious Studies major on acid. We still think about Morrowind daily, and we seek new experiences which will replicate the sensation of confronting Morrowind anew.

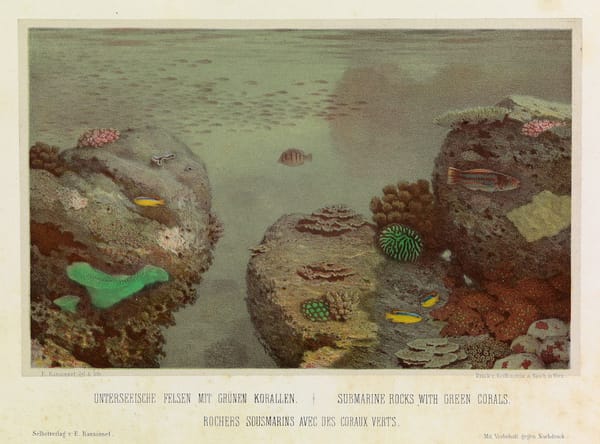

The Tainted Cup by Robert Jackson Bennett is a type of Romancing Morrowind, whether Bennett intended it or not. Concerned with a bureaucratic murder mystery, the book takes place in a fantastical swampland threatened by eldritch monstrosities, covered by unusual plants and mushrooms, and dripping in that perennial poor-taste sci-fi/fantasy sauce: Orientalism. In that way, it is like Morrowind, and in that way it is a little bit uncomfortable and perhaps out of step (too in-step?) with Our Times.

The story kicks off with Dinios “Din” Kol, an anxious young functionary with an artificially enhanced eidetic memory and a secret print disability, investigating a murder on behalf of an eccentric government investigator named Ana Dolabra. Dinios discovers that the functionary died via genetically-engineered super-grass, a rare strain supposedly eliminated by the government after its original disastrous creation. Ana and Din dig deeper, uncovering layered conspiracies implicating the most powerful aristocratic family in the land. Meanwhile, monstrous sea-dwelling leviathans threaten landfall, a threat made worse by the conspirators’ plotting. The rollercoaster of twists and turns in the investigation forces our heroes to confront a series of gruesome killings, a murderous super-assassin, and a sexy dancer with pheromone powers. Yes, all the hits. Bennett frames the tropier and more familiar elements of the story within his detailed secondary world, lending the tropes the specificity required to re-enliven them.

Crucial to this secondary world is The Empire for which Din, Ana, and the murder victims all work. Bennett leaves us with no doubt about the authoritarian superstructure of this government, but he also leaves us with a worryingly full-throated endorsement of that superstructure. When Ana wants to hearten Din’s resolve after they are nearly killed by the evil conspiring aristocrats, she says “The Empire is strong because it recognizes the value in all our people. Including you, Dinios Kol. And when the Empire is weak, it is often because a powerful few have denied us the abundance of our people” (386, emphasis in the original).

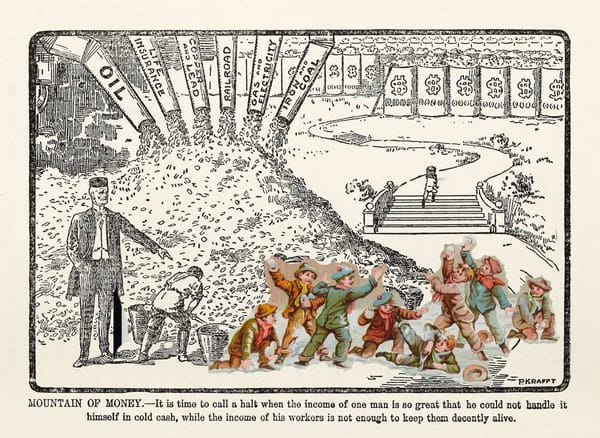

Perhaps this sounds like some “eat the rich” populism, but there’s no eating the rich without also eating THE LITERAL EMPEROR. To me it sounds more like this: “Fear not, humble citizen, for The Empire is your sole protector against incomprehensible evil rising from outside our enormous walls. Whatever problems we have, the real fiends causing them are the rich, greedy aristocrats who manipulate the government from behind a mysterious smokescreen, hidden from the common man…”

Oh, the more I articulate it, the less good I feel. I'm not one to go white-knighting for aristocrats as a concept, but I have a certain sensitivity to the argument that our beloved dictatorship is being corrupted by the influence of secret wealthy cabals. That's because it is a classic anti-Semitic canard which informs contemporary nutbar-core ideas like QAnon.

While I love excusing the fucked-up beliefs and behaviors of imaginary people by examining them in the context of their imaginary worlds, contextualizing a real guy’s beliefs in the real world leaves me with no excuses. Bennett helpfully left me an afterword declaring “how America is now terrified of building stuff…Regulations have their uses, but we cannot allow them to form the jar…to trap us” (410). We can’t allow regulations to trap us. We need more of a builder’s spirit, like the heroic builders who constructed the Empire’s tremendous walls under the oversight of enormous immortal dictatorial functionaries serving a god-emperor! Tremendous walls have famously never trapped anyone.

I’m left in a bit of a bind here: The Tainted Cup is quite a good book in and of itself--entertaining, twisty, and fantastical. It appeals to me with its freaky and mysterious world. I just want to luxuriate within its fernpaper-walled estate, wearing a silk robe and a conical hat, smoking totes not Chinese opium, and pretend to be a mysterious elf or a guy with fungally-transmitted savant mutations.

But I won't.

Sometimes you can’t just Romance Morrowind. Sometimes you have to sit down and think about how it’s seducing you. Otherwise you end up one of those guys on YouTube who posts about how adding a non-gendered toggle for character body types to the Oblivion Remaster is a type of Marxist cultural imperialism.

Right now it seems quite like Bennett is huffing crypto-fascism like an un-self-aware Norman Spinrad. I can’t possibly endorse something which produces that most exceedingly risible worldview: king-loving libertarianism. There are more than enough dipshits peddling that already.

Alien Clay by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Alien Clay is Tchaikovsky’s second novel nominee this year, and since I enjoyed Service Model surprisingly well, I wasn’t dreading this one. Better yet, Alien Clay didn’t disappoint me. Concerning the torments, adventures, and recollections of a professor-turned-political prisoner imprisoned in a work camp on another planet, Alien Clay ambitiously attempts to fuse science adventure, political manifesto, and alternate consciousness meditation into one mediumish book.

The core narrative: Professor Arton Daghdev and other imprisoned dissidents are forced by the totalitarian Mandate government of Earth to investigate the mysterious ruins on the planet Kiln, so that the Mandate can prove all life eventually evolves into human beings. This is the anthropocentric core of the Mandate’s ideology. Instead, the prisoner-scientists discover an ecology which is inconceivable from the blinkered Earth First standpoint of the Mandate. This ecology changes them in unexpected and powerful ways.

I used the word “attempts” above to describe Alien Clay’s genre mélange because I don’t think it is completely successful in carrying off all the different modes Tchaikovsky invokes. If you are interested most deeply in the surreal alien life of Kiln, you will find the narrator spends a great deal of time pondering the nature of anti-authoritarian praxis. If you are interested most deeply in speculative anti-authoritarian praxis, you will find the narrator spends a great deal of time describing freaky worms and weird trees. If you are one of those people who needs the narrator to have a quirky voice and good quips, I must break the news to you that Daghdev is a long-time professor of ecology, and Tchaikovsky bravely refuses to compromise the voice of an exceedingly middle-aged professional pedant.

However, if the metric you are using to evaluate Alien Clay is not “Is this an airtight work of entertainment literature?” but rather “Did I, Your Ween, like this book?”, then I will assure you that this book is completely successful. While there were moments during the long critter descriptions when my attention flagged, I held fast to the elements which most interested me (and I did enjoy a sold 67% of the critters) and arrived at a final act which was stirring and unsettling in equal measures. Tchaikovsky deploys the science fiction conceits in his premise to serve as a testing ground for new forms of political consciousness. Daghdev’s innate, urgent, but compromised resistance to the Mandate and its minions is elevated by the alien biology which he embraces. He transforms, not from a neutral party into a revolutionary, but from a neutralized revolutionary into a reinvigorated one. He allows himself to be blown up, mutated, expanded, transformed into a more effective political being.

I loved this. Though I saw most of the key plot revelations coming from early in the novel, watching them slot into place was eminently satisfying. Tchaikovsky’s commitment to the bit makes the plot more than the sum of its parts. I loved the intense focus on the challenge of maintaining connection and attachment in the face of political violence, and I loved the way Tchaikovsky just politely refused to insert any romantic plotline. Much of the book is spent probing Daghdev’s relationships to the other prisoners and to his oppressors, but not in a way which can be boxed up and stored neatly. Daghdev discovers many new facets of himself and his compatriots, and their mutual acceptance is something outside any of our existing relationship paradigms.

After I finished Alien Clay, I continued to consider its closing moments, the Big Choices made by Daghdev and his fellow revolutionaries. Daghdev himself notes that the final stages of their revolution will look unsettling and potentially dangerous to the outside observer. Their new way of living and thinking is a threat to the norms of even those who hate The Mandate. But the journey he’s taken across Kiln, the journey on which I followed him, is structured so as to convince us both that what he plans to do is right, that the only solution to world-crushing tyranny is transformation. We must transform into shapes around which fists cannot close. We don’t have magic mind-altering airborne plankton on hand, but we have many other interesting tools, not least of which is science fiction. I appreciate Tchaikovsky reminding me of this, now of all times.

My Hugos(-Induced) Breakdown

The 2025 Hugo Best Novel nominees almost killed me. I can never do this again. The whole time I felt as if I were climbing out of the Sarlacc Pit from Star Wars, but the sand was mediocrity and the tentacles were under-engaged premises.

I feel deranged about Someone You Can Build a Nest In winning the Nebula Award for Best Novel. I want to peel my own eyelids off. I can’t believe the Nebulas would betray me like this. Nebulas, you were supposed to save the Jedi, not destroy them.

It’s looking more and more like next year we’ll be reading the Clarke shortlist.

But then again I also feel like I’ve been bullying the Hugos too much…As a science fiction fan myself, I must assert our right to be dumb and have mediocre taste. I decided to run the numbers on all the SFF I’ve read so far this year so I could fairly and quantitatively evaluate both the material and the standards to which I’ve subjected it.

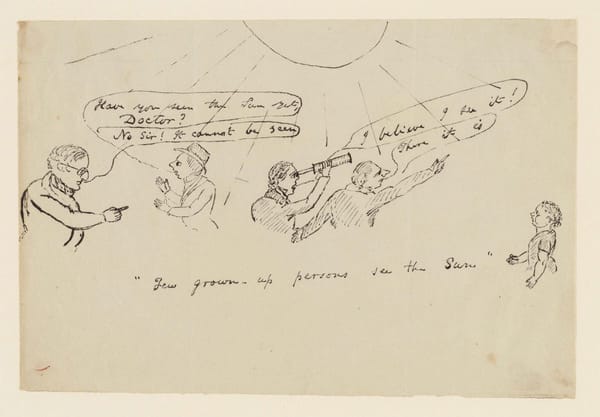

What my analysis revealed is a conclusion that ought to have been fairly obvious, but which I missed due to an overwhelming naivete: all the older SFF books I’ve read this year are books which already stood the test of time, or which came personally recommended to me by a friend or family member (or Peter S. Beagle glazing his own book in the foreword to his other book, but for the purposes of this census, Peter is friends & family). Meanwhile, the newer books came recommended from impersonal and popular sources like the Hugos Shortlist or the annual NPR Booklist. No churned-up annual list can outdo the relentless brooms of time, which eventually sweep away the temporarily-lauded chaff and leave behind the lasting works (and sometimes also sweep away worthy works by marginalized authors who must then be recanonized later, etc. etc.).

The chart also puts into perspective how few legitimately terrible books I actually read, despite my vociferous and detailed protestations. 2.5 is the mid-range of our scale, the C of our letter grade system, and as you can see I’ve only read two books I’d rate lower than that. Most of the books I’ve complained about here on the blog were actually B- books. Unfortunately I am, like the demented Boys British Boarding School-esque instructors who created me, unwilling to laud a B- student, even though they are so normal and nice and will be perfectly successful in life. Truly, the cycle of abuse goes ever-unbroken.

A sane person would come to the end of this reading quest and rank the damn books. This should be easy to do, since I already rated all the books on a 1-5 scale. However, the second most enjoyable/interesting book was also the one with the most weird sublittoral bootlicker anti-Semitic vibes, so I wouldn’t want that book to win the Hugo. I would want to yell at Robert Jackson Bennett from across a hotel ballroom during the Hugo Awards Ceremony, though.

If you ask me which book I want to win the 2025 Hugo for Best Novel, I will say Alien Clay by Adrian Tchaikovsky. If you ask me which book you should take to the beach for a fun read, I will say Service Model by Adrian Tchaikovsky. If you ask me which books are perfectly fine but simply not for me, I will say The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley and A Sorceress Comes to Call by T. Kingfisher. And then there are two other books.

If you ask me which books had cartoonishly evil abusive mothers that were so cartoonish they stopped being interesting, I will say A Sorceress Comes to Call and Someone You Can Build a Nest In. If you ask me which books had a fairly dull romantic plotline which reminded that I don’t care for Romance as a genre, I will say Someone You Can Build a Nest In and The Ministry of Time. If you ask me which books had a troubling lack of questions about the world in which they were set, I will say A Sorceress Comes to Call and The Tainted Cup. If you ask me which books had very en vogue and consequently somewhat dull and lifeless Trauma Plots, I will say A Sorceress Comes to Call and Someone You Can Build a Nest In, and a little bit The Ministry of Time. And then there are two other books.

But if you ask me which book I truly enjoyed, which book stuck to me like an alien symbiote and pushed me to consider the next world--after the revolution--I will say Alien Clay.