Little, Big by John Crowley

Architectonically Sublime, or What?

After many years of manifesting it into the used bookstore shelves before me, I finally located and acquired John Crowley’s Little, Big, in a lovely, aged first paperback edition. You might ask, “Why didn’t you just buy the book online or something, if you wanted to read it so bad?”, but what you fail to comprehend is that science fiction and fantasy fandom is a type of vision quest. I had to wait for Fate to determine I was ready for Little, Big.

Was I ready for Little, Big? Bruv, I don’t know.

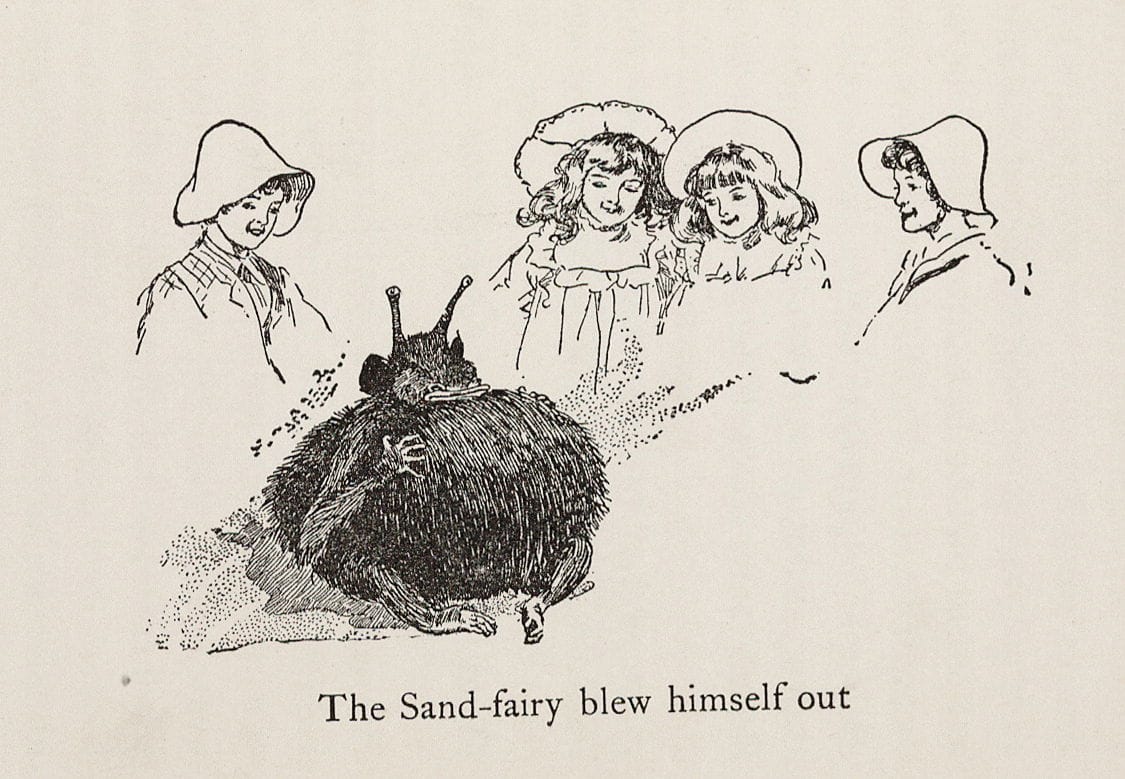

This book reminded me of The Innkeeper’s Song by Peter S. Beagle in that it was wondrously composed on a sentence level and completely baffling and weird on a content level. At no point during my reading of this book could I have told you what was going to happen in this book, let alone what the plot of the book was. The pleasure of this book is luxuriating in Crowley’s lushly described fey-touched world. Do not read it if you are a pacing hardliner.

I’ve been trying to think of a pithy X-Meets-Y way to describe Little, Big, and I’ve come up with two analogies:

- Little, Big is like if John Boorman’s 1981 film Excalibur took place in 1981 New York, instead of Arthurian England.

- Little, Big is like if Francis Ford Coppola’s 2023 terrible science fiction movie Megalopolis were a good fantasy movie instead.

Do what you can with that.

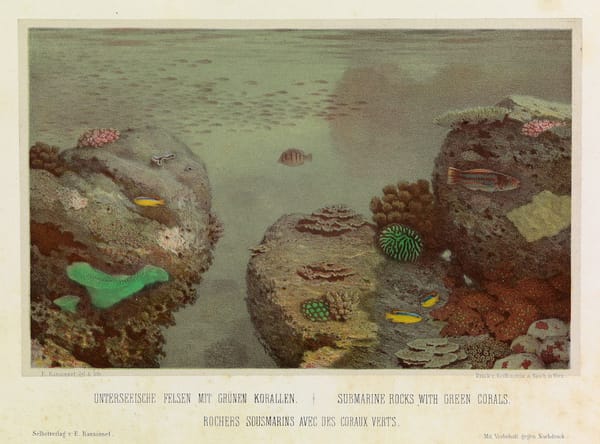

Theoretically, Little, Big is about the Drinkwater family of Upstate New York. The Drinkwaters are a messy and sprawling clan of dilettante occultists and Theosophists who live in and around a mysterious five-faced house called Edgewood. Edgewood has four floors, seven chimneys, three-hundred sixty-five steps, fifty-two doors, etc. etc. It may be the Door to Faerie.

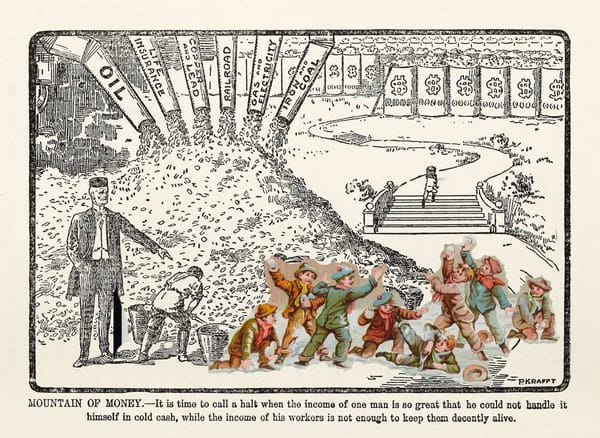

Some sections of the book concern turn-of-the-century patriarch John Drinkwater, his teenage wife Violet Bramble, and their suitably messed-up children. Other sections of the book follow the marriage of outsider Smoky Barnable to John Drinkwater’s very tall granddaughter, Daily Alice, some time in, I believe, the late 1970s or early 1980s. Still other sections of the book track Smoky and Daily Alice’s son Auberon as he tries to become a television writer in The City. I think, based on math and mood, that Auberon’s trials begin some time around 2013. Crowley anticipates that future time from his 1978 vantage with sometimes exceptionally clear-eyed vision and other times cringe-inducing whiffage.

Everyone in the Drinkwater family is waiting for their Destiny to come to fruition (except Smoky, who doesn’t believe in Destiny), as the Drinkwaters have a promise from The Others that they will play a critical role in the future of the world. And they really do, but we will walk 500 pages before we find out what it is.

Oh, also Emperor Frederick Barbarossa is an essential character in this story. I had to finish the book and then read an interview with John Crowley to understand why, but once I did, I was deeply shaken by what John Crowley had divined about America’s future.

If this sounds insane to you, sure. But the thing about John Crowley is that he is a perhaps peerless sentence-crafter. Like, Jesus wept at the perfection of this man’s compositions. Some of his sentences are perhaps too much, I’ll concede this, but I have maximalist tendencies for which I won’t apologize, and so I reveled in Crowley’s craft on every page.

I will not suggest that John Crowley is a peerless plot-crafter, nor should he have to be. This book moves like a dream, a vision, or a hallucination, its meaning only discernable in your encounter with it.

Like a dream, Little, Big also surfaced some uncomfortable and unpleasant things which sit entirely well with a reader from the actual 21st Century. There is some very dated and demeaning language used in reference to gay and Black people. The only major Black character in the book is arguably and embarrassingly of the Magical Negro type. There is also a notable amount of incest in this book, often treated quite lightly. I’m not an incest-in-literature afficionado, so it always feels like a lot to me, but this particularly felt like a lot-a lot.

But I can’t say that these ugly facets of the book didn’t completely track with regards to both the age of the book and its subject matter. Dreams come up out of the low places in our minds and sometimes they can be very unpleasant to view. Little, Big has at least five faces, and I can’t love them all.

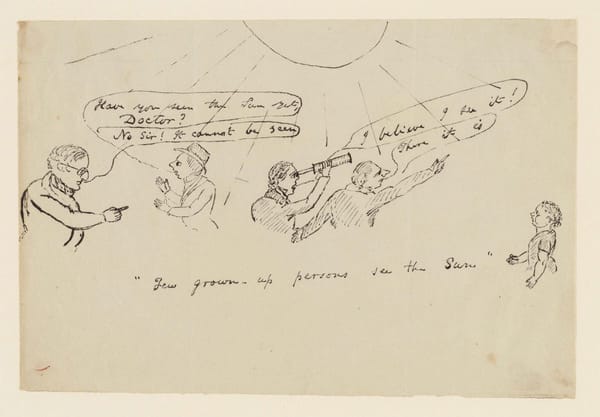

The reason I read this book is because I kept hearing about it as a touchstone not for fantasy fans or publishers, but for actual fantasy writers, an influence on the people who influence me. On Little, Big’s Wikipedia page there’s a hysterical quote from a fantasy scholar who calls the book “a work of architectonic sublimity”. What the hell does that mean?

Well, now I know. I finished Little, Big, and though I didn’t love every page or every idea, I was moved by it, confronted by it, uplifted by it, unsettled by it. I think and think on it. It has given me the kind of intellectual challenge that I have times missed from contemporary fantasy with its didactic tendencies. I wrestle with its meaning and its intent days after finishing it.

Little, Big is a Romance in the chivalric sense, speaking on the “Matter of America” with a clear and awesome/ful voice. Its final notes echo out and out. My ears are still ringing.