Recently Reading Peter S. Beagle

I encountered the work of Peter S. Beagle for the first time recently. Yes, I’ve never even read The Last Unicorn. Am I a Fake Fantasy Fan? Indubitably. I have seen the animated film, which is weird and yet touching and yet baffling. I know that Peter S. Beagle wrote the script for it, and I also know that screenwriting is hard. What I did not know was that he’s really into unicorns generally.

I have learned a great deal about what’s going on in the mind of Peter S. Beagle since confronting The Overneath and The Innkeeper’s Song. What an imagination you have, pepaw…

The Overneath

I decided to read The Overneath instead of going straight to The Last Unicorn due to my resolutely contrarian nature. I will never approach someone at their best when instead I can approach them through some tertiary work instead. The Overneath represents, I presume, the best of Beagle’s output in this century, and the stories overall suggest a mature, late-career writer who has a strong sense of who he is and what he likes to write about. While some of the stories weren’t my vibe, the best of them were arresting and deeply tender, and often about unicorns.

For a writer of fantasy, a genre often accused of being overblown and vaguely fascistic, Beagle seems most at home writing in a wistful, domestic sort of mode free of bombast. I’m allergic to most material marketed today as “cozy” because of its general lack of interesting events, characters, or scenarios, but I can see how one might consider Beagle a forerunner to the cozy genre because of his attention to the intimately quotidian. However, I enjoyed Beagle’s stories much more than I enjoy the general cozy fare for two reasons: 1) his sincere attention to his characters’ emotions allows him to capture the force and agony of everyday life, and 2) he’s not afraid to go to a completely fucked place if he feels it’s appropriate. Stories like “Kaskia” reminded me of Theodore Sturgeon’s work. A lonely loser uses a high-tech laptop to make contact with a mysterious alien being, and thoroughly misapprehends who she is and what kind of relationship they have. And yet the revelation of their actual connection is liberatory, not crushing. Though Beagle is not such a provocateur as Sturgeon, he also puts a spotlight on the lonely and the disaffected in a humane and empathetic fashion.

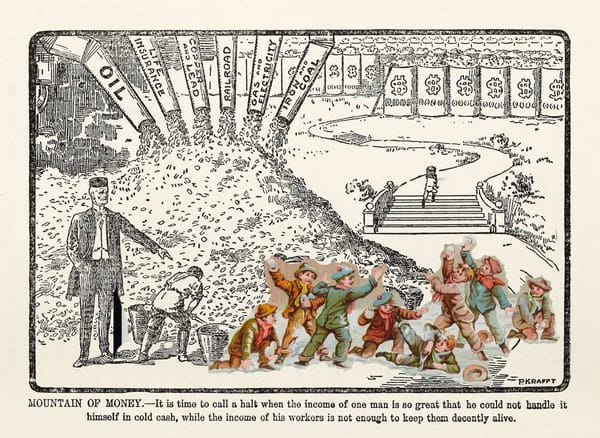

In terms of pure storytelling, “Great-Grandmother in the Cellar” and “Music, When Soft Voices Die” were my favorites. Great-Grandmother, a terrifying undead skeleton, rises up to protect her family when her great-grandson calls, and the common fantasy division of Big Good vs. Big Evil is shoved aside for a delicious Evil vs. Evil magical duel. Beagle creates a significant space for the kind of moral uncertainty in which classic folk tales, myths, and fairy stories revelled and to which modern fantasy writing is furiously allergic. In “Music”, Beagle mounts a steampunk science mystery that suddenly downshifts into a probe of the inherent sorrow of existence, the unconsidered torment of every person on Earth. Beagle makes this extra-poignant by viewing it through the lens of the historic marginalization of Jewish people. I appreciate that Beagle chose to engage with the disturbing and cruel tendencies of Victorian England. When I ponder which SFF genres are mature enough to provide meaningful social commentary, I don’t think of steampunk first, but that is evidently on me because Beagle makes the Victorian alt history setting work hard here.

Of the unicorn stories included in this volume, “Olfert Dapper’s Day” is the best of them, a caper at first, then a frontier survival struggle, then a bittersweet doomed romance, and finally a redemption story for an inveterate swindler. While the other two unicorn stories in The Overneath have an entertainingly storybook quality, “Olfert Dapper’s Day” digs into the specifics of a man who is both charming and corrupt and, as a good story should, it puts the screws to him until he acts in an interesting way.

I could go on: “The Green-Eyed Boy” is a wonderful, uplifting, honest story for anyone who’s felt terminally behind or incompetent in their chosen field; “The Way It Works Out and All” is a touching tribute to a real life friendship, inviting the reader in to join the participants in their comradeship; “The Queen Who Could Not Walk” wrings fresh tears out of the old, old, old forgiveness story; and so on. Fundamentally, Beagle is an excellent storyteller. His stories betray some pepaw-typical flaws here and there: a few stories tilt dangerously close to Orientalist deployments of Asian mythology, and he doesn’t always provide his female characters with dynamic roles in comparison to his male characters. These foibles are not so severe as to rob his work of credibility in my eyes, but they remind us that even the finest storytellers have their weaknesses and oversights, which is why we should welcome the diversification of genre writing. Truly great voices won’t be stifled by the addition of other perspectives, but rather enriched by comparison, contrast, and dialogue.

The Innkeeper’s Song

Then Peter S. Beagle hit me with this crazy book, which I believe he has called his best work. That’s probably true, in that it so completely achieves the ends that Beagle set out to accomplish that it is somewhat alienating to the reader, who does not know what he’s trying to convey until they get to page 300 or so.

This is not a good book for an impatient reader and it is not an easy book to describe via its plot. A young woman in a rural village dies, is reanimated by another woman, and the two of them take off, pursued by the dead woman’s fiancé. All three end up at an inn called The Gaff and Slasher, where they are joined by a third woman, a magical fox, a stable boy, an innkeeper, and a dying wizard. Everyone I’ve listed, except the wizard, is a POV character, as the narrative is relayed through rotating sections of first-person narration. The two middle-aged women, students of the dying wizard, seek to save the old man; the young fiancé seeks to reclaim his undead and amnesiac bride; the stable boy seeks the love of all three women, as well as answers about his own murky past; the fox seeks chickens; the innkeeper just wants all these freaks out of his inn.

The reader weaves in and out of this crowd of characters with Beagle as a guide and a sort of interviewer, thanks to the pointedly conversational narration provided by each character. Beagle artfully leverages this intimate mode of storytelling to produce the same type of excruciatingly subtle exposition and worldbuilding which has made the Souls fandom so sick in their minds. Almost every single paragraph is doing double service simultaneously relating the events of the story and revealing the motivations, backstory, and personality of each narrator-character. On a writing level, Beagle bowling an all-strikes game. Every time he starts a new paragraph, you’re like “he can’t possibly hit all those pins” and then all the pins eat shit. It’s crazy, and it’s also a little bit exhausting. How much can a man slay before you no longer marvel at his slay, especially when you can’t see what he’s slaying towards?

The revelation arrived just in time for me, and I realized (to continue to draw out this agonizingly contrived metaphor) that with each bowl Beagle was knocking down the pins in such a fashion as to produce a reasonable approximation of the tune of “Claire de Lune”. I don’t know if that makes any sense as an explanation, but it is hard to explain why I found myself so hideously moved by the conclusion of this book, why I felt so strongly that all my time was repaid at the closing despite the fact that I had no sense of where we were headed at any point before then. The Innkeeper’s Song offers a deeply relational exploration of its characters, a commitment to knowing them in the context of their world and discovering them over time. In the end it becomes a meditation of the meaning of death and an encapsulation of the unpredictable consequences of devotion, affection, and courage. I feel fairly insane about it.

I would be remiss if I did not note, for the health of potential readers, that there are some fairly weird sequences in this book, most notably an extended four-way sex scene which includes an unexpected mid-coital sex/gender reveal. This is obviously a bit of a touchy subject, but it is a surprisingly compelling sequence, if out-of-nowhere and heavy with weird implications. The character whose sex is unveiled is never rejected or questioned by his partners, and indeed the encounter provokes one of them to rethink his own sexuality a little in a constructive fashion. On the other hand, two of the participants are young adults/teens and two of the participants are adult-adults, and that was rather scuzzy. It is not a sequence of events which is easily dissectable using contemporary terms and ideas about sex and gender, and so I’m not entirely sure how to take it apart meaningfully in this context. Phenomena precede and exceed language. The world of The Innkeeper’s Song is not like our own, nor should it be. But if it is very important to you to have those words and ideas as scaffolds when engaging with sexuality, then this is not a book you will enjoy.

But I enjoyed this book! Despite everything, I did enjoy it, because Peter S. Beagle knows what he’s doing when it comes to writing. He let his mind travel to some baffling and mysterious places, and some of those places weirded me out, but it was an interesting trip. He conjured up a world and its people, and he gifted it to me, warts and all.